Bernie Flint tribute: “He’s always done well — and you always knew he was around”

He quit training in 2023 after 3,551 official wins but remains an owner

Video: Picture this! Flint’s 54 years as a thoroughbred trainer in photos

Story by Jennie Rees, Kentucky HBPA

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Wednesday, June 25, 2025) — Bernie Flint — the former New Orleans detective who became one of Kentucky’s all-time winningest trainers — exuded a larger-than-life persona during more than 50 years at Midwestern racetracks. Hanging up his tack in November 2023 surely ranks among the quietest actions he’s ever taken.

Now 85, Flint did not quit training 1½ years ago because 54 years doing anything is plenty. Rather, health issues kept him from spending the time at the barn he felt his horses and owners deserved. Flint opted for a silent exit: He didn’t ship horses as he normally would have from Churchill Downs to the Fair Grounds for the 2023-2024 winter meet. Thus, an era unceremoniously ended.

“He’s never done anything quietly in his life; this might be a first,” joked Frank Brothers, a nationally prominent trainer who retired in 2009. Brothers was a kid in New Orleans when he first met Flint, then a police officer, at quarter-horse shows.

“He liked the horses and the horse shows,” Brothers said. “He rode some, but he’s a big guy, so it wasn’t quite as easy for him as us smaller guys. He got into thoroughbreds and did well through the years. He’s a good horseman. He’s always won races, and he’s always done well — and you always knew he was around.”

Flint — booming and looming at 6-foot 3½ inches and, at his peak weight, 245 pounds — completed his training career officially with 3,551 victories, which ranks No. 28 all time in North America. That includes 501 at Churchill Downs, at the time making him the sixth trainer to reach 500 under the Twin Spires. Fittingly, Flint went out a winner, with Bright Spark his last starter on Nov. 10, 2023, at Churchill.

However, Flint hasn’t left horse racing completely. His L.T.B. Inc. (named for youngest son Lance, wife Terri and himself) continues to breed, own and race, predominantly in Indiana and in partnership with long-time client Ron Hillerich.

“There are certain people who are bigger than life, and he’s one of them in the racing business,” said Hillerich, who had Flint as his trainer almost exclusively since the Louisville attorney got into horse ownership in 1992. “Everybody who knows him loves him. He’s just that kind of guy.”

Unlike some other Kentucky trainers who got out of the business the past few years, Flint didn’t run out of owners or horses. He had about two dozen when he stepped away, he said.

“The age caught up with me. I really didn’t want to have to explain it to everybody,” Flint said in a phone conversation from his Louisville home. “I just quietly left. I thought that would be better.” Overall, he said, “I’m doing pretty good. I’m still here.”

Flint appreciates just how difficult it is for an octogenarian to continue to manage a racing stable, saying this of 89-year-old D. Wayne Lukas before news this week that the industry icon had been hospitalized and won’t return to training: “I think Lukas is the toughest man I’ve ever seen in my life. Because he’s still going.”

Flint, recently diagnosed with treatable cancer, remains awfully tough himself, saying, “But I’m all right. Just got to get rid of that cancer and I’ll be fine.”

Hillerich acknowledged that some of the fun is gone from racing with Flint no longer training.

“The biggest part of the racing I’ve been involved in was being able to go to the backside and visit with Bernie in the morning,” Hillerich said. “Bernie holds court there — used to — in the tack room. I miss that…. He’s one of the best horsemen, and he doesn’t get the proper credit. He’s got that eye for a horse that a lot of horsemen don’t have. He’s a very smart man, very intelligent. He’s not only my partner, he’s one of my very best, dear friends.”

The man also is a world-class talker. If you need to ask Flint a simple question, it’s best to budget a minimum of 20 minutes.

“Oh yeah, if not longer,” said long-time assistant Georgia Jackson, who worked for Flint for 23 years. “When it came to an issue he liked talking about, he’d just keep talking. That’s true. And he made a lot of sense. People listened to him.”

Started smoking cigars after his first autopsy as a young cop

The big man rode a big pony on the track up until his final few years of training. Then Flint indeed held court in his tack-room office, inevitably smoking a fat stogie. He still smokes cigars, a practice that began many years ago after witnessing his first autopsy as a homicide cop, he said. The victim stunk something awful, but Flint’s senior partner, smoking a cigar, was unfazed.

“He said, ‘I smoke this cigar, and it kills the smell,’” Flint recalled. “I asked the guy doing the autopsy, ‘Why’s this guy smell so bad?’ The doctor turned around and told me he had only three or four months to live anyway — he had black lung. I asked what that was, and my partner told me, ‘That’s what you get for smoking cigarettes.’

“I went out of there with a full pack of cigarettes in my pocket. I threw it in the trash can, and I never smoked another cigarette since then. I smoked cigars. I spent only one year in homicide. I could type around 80-90 words a minute on a manual typewriter. The problem was, I couldn’t stand the smell.”

Trainer Bret Calhoun has known Flint for years from both Kentucky and Louisiana.

“Bernie’s got a big, booming voice, a big man,” Calhoun said. “He did kind of go away quietly. Tough man. Did a little bit of everything in his life from police officer to training horses. Very, very successful horse trainer — and loved the game. I hate that he’s gotten out of it. He was a lot of fun to be around in the morning and at the races. He was very entertaining.”

Flint told a turf writer many years ago that he was going to retire at age 60 and turn the stable over to his oldest son and long-time assistant, Steven. (Another son, Scott, is a horse-shoer in Kentucky.) At 61, Bernie still insisted he didn’t want to be what he called “a social-security trainer.”

However, the prospect of having a Kentucky Derby horse with Outofthebox, runner-up in Gulfstream Park’s 2001 Fountain of Youth (then a Grade 1 race) and Florida Derby (G1), delayed Flint’s alleged retirement plans. A fifth in Hialeah’s Flamingo Stakes dashed the Kentucky Derby dreams, but four races later Outofthebox upset heavy favorite E. Dubai in Louisiana Downs’ Super Derby for what would be Flint’s only Grade 1 victory.

22 years later: So much for not being ‘social-security’ trainer

Flint blew past social-security age and trained another 22 years. With a large claiming operation much of his career, he won at least 100 races each year except twice between 1988 and 2004. His horses earned at least $1 million in a season 23 times from 1988 through 2019.

Steven Flint estimates his dad trained as many as 90-95 horses at his peak, back when that was a massive operation and not the norm for the top stables.

Although Flint’s official win total as a trainer stands at 3,551 dating to 1972, according to industry data keeper Equibase, the Blood-Horse and other publications list his first thoroughbred race as coming in 1969 at the Fair Grounds. Flint and his sons say the win total is much more than what shows officially. Not only do Equibase statistics not go back that far, they say, the elder Flint was rolling in an era where tracks required the trainer to be on hand so many days to run horses in his or her name. With a large stable spread out among multiple tracks at the time, Flint horses often ran with an assistant listed as trainer, they say.

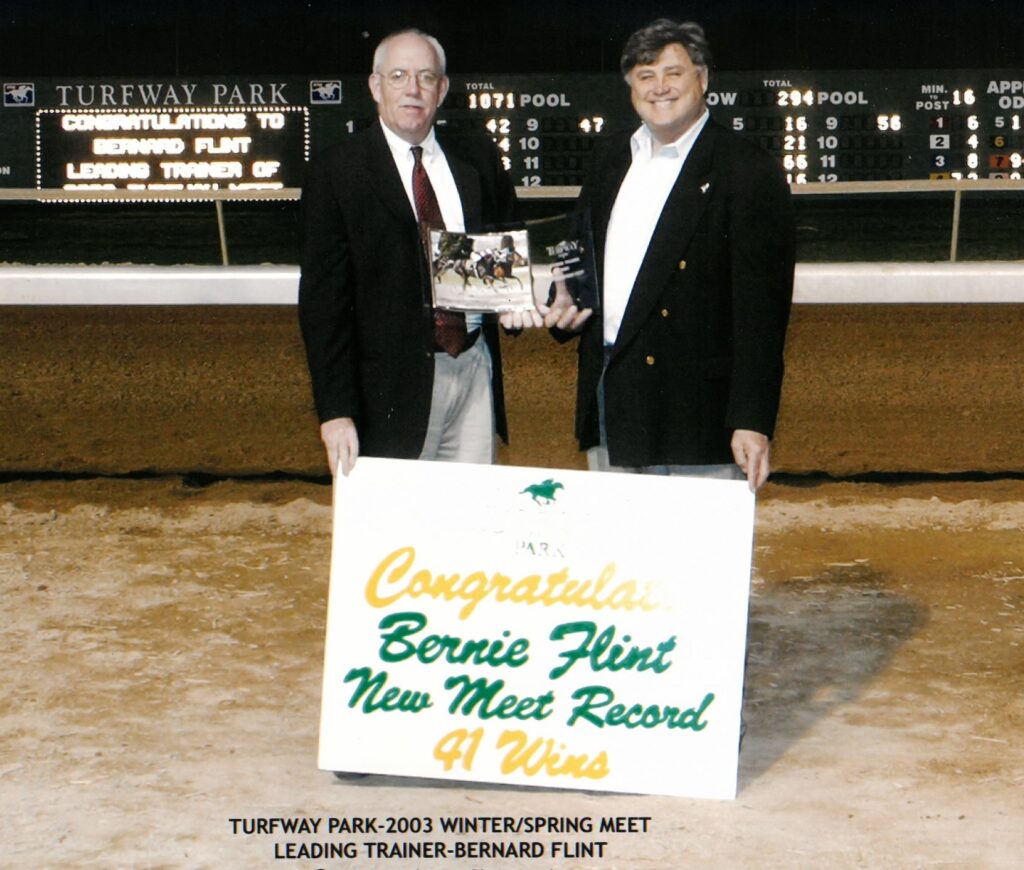

Flint, who moved his main base to Kentucky in 1980, was honored by the now-defunct Kentucky Thoroughbred Media every year from 1998 through 2003 for winning the most races in the commonwealth. He earned meet titles at Turfway Park a then-record 20 times as well as being the leading trainer at Churchill Downs, Keeneland, Oaklawn Park, Hoosier Park, Ellis Park, Canterbury, Sportsman’s Park and Balmoral, according to the Blood-Horse. He also won multiple training crowns at Jefferson Downs.

Flint-trained horses won 28 graded stakes, from Top Corsage in Churchill Downs’ 1988 Falls City Handicap to America’s Tale in Gulfstream Park’s 2019 Inside Information. His most successful runners included 14-time winner Hurricane Bertie, who has a stakes named for her at Gulfstream, and Swept Away for the Klein family of Louisville. Runway Model, winner of Keeneland’s 2004 Alcibiades, went on to take third in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies before capturing Churchill Downs’ Golden Rod for owner Dr. Naveed Chowhan. The homebred One Mean Man won five stakes and his full sister Mizz Money won four for Flint and Hillerich.

“One thing I did do is we did beat at Keeneland,” said Flint, pointing to He Is A Great Deal’s eight-length victory in the slop in the 1984 Lexington Stakes over the future Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes winner. (Flint sold He Is A Great Deal for a reported $200,000, but as the gelding’s career waned, bought him back privately to give him a retirement home. He Is A Great Deal died in 2009 at age 28 on Scott’s farm.)

“My mother is 91 years old, and she most probably bet on every horse Bernie Flint ever ran, whether it was Churchill Downs or, obviously, Fair Grounds,” said trainer Al Stall, another native New Orleanian, who, like Flint, has made Louisville his main base for years. “I don’t really know

why. I guess he was winning and caught her eye.”

Even if her son had a horse in the race? “Maybe she’d do an exacta,” Stall said. “Every time she’d say, ‘I’m betting Bernie Flint’s horse.’ She did that for 40 years.’”

Flint’s dad was a Russian emigrant who ran a taxi company and then a clothing store. Flint graduated from Loyola University on a police scholarship with a degree in criminal justice. He said he started out as a patrolman in the French Quarter with an acting rank of detective, having been fast-tracked to the detective bureau because his impeccable typing was coveted in a department short on secretaries.

“In those days, the guys were hunt-and-peck. I had abilities with the typewriter,” he said. “I could type as fast as you could talk.”

“There are a lot of stories about me; most of them aren’t true.”

Flint retired from the force in 1976 after 16 years, including two years heading the burglary division, to become a trainer full-time because, he once told a reporter, horses “don’t shoot at you.”

There are racing participants who say they saw Flint sleeping in his police cruiser until the track opened for training or wearing his uniform aboard his pony. That’s just racetrack lore where facts are optional, Flint says. He does admit to running out to the track in uniform to saddle horses for races.

“I did have the uniform on, because I had to go to work,” he said. “I’d put an overcoat on to saddle a horse or something. I would not sit on the pony in uniform with an overcoat; I wasn’t stupid. I had a small outfit. I didn’t have anyone else to saddle the horse. There are a lot of stories about me, but most of them aren’t true.”

By contrast, he said of his version of events: “It’s not stories; it’s truth. That’s the way it was.”

Said Bryan Krantz, who literally grew up at and later owned long-gone Jefferson Downs in Kenner, outside of New Orleans: “He just always had that big personality…. He came at (training) the old-school way. He learned how to work with horses that had issues, fix them and get them comfortable, and then they’d win their races.”

Flint’s equine competition started out in barrel racing and the other disciplines at the quarter-horse shows. He progressed to running in match races at the bush tracks sprinkled around Louisiana’s Cajun country — rough and tumble competition where a man might have to fight to get his money if he won, he said. With a barn on some lakefront property he got from his mother, Flint said he kept his horses fit by attaching a lead shank and letting them swim in Lake Ponchartrain. “I couldn’t get anyone to come out to gallop them on the levee,” he said.

With his NOPD job, Flint wasn’t able to run very often at Delta Downs’ sanctioned quarter-horse races near the Texas border. He looked for a way to stay home and race at Jefferson Downs and the Fair Grounds.

“I bought a horse called House Seats from J.R. Smith for $1,500,” he said. “He won like eight races for me. I fell in love with the thoroughbreds.”

Along the way, Flint also became a pilot, at one time owning two airplanes, he said.

“I flew Randy Romero to Delta Downs in order to be leading rider (in the country) when nobody else would take him, the weather was so gawd-awful bad,” Flint said. “I can’t believe I did it. But I did it for Randy. I was careful, but like I told him, ‘We might get there, or we might not. I might get you home, and I might not.’ He made it there, and he did ride. But the horse bolted on the turn. He broke his leg and got stuck there. I jumped in my plane and flew back home.”

Flint gave up getting on the pony only in his last few years of training, he said, after his doctor made it clear that he might be paralyzed if he fell.

“I rode every day, just like Lukas,” Flint said. “I mean, I came up a little short and Lukas kept on going. Old-time trainers are hard to find, but you’ve got to have your health. I felt I couldn’t do the job 24/7 because of my health, and I just hung it up and never said anything.”

Breeding, racing in Indiana — thanks to Unbridled Express

Today, the horses he owns with Hillerich (and a few others Flint owns with a couple of long-time clients) are trained by Genaro Garcia, whose main base is Horseshoe Indianapolis but who also races in Kentucky. Flint and Hillerich are prominent in the Indiana thoroughbred breeding industry.

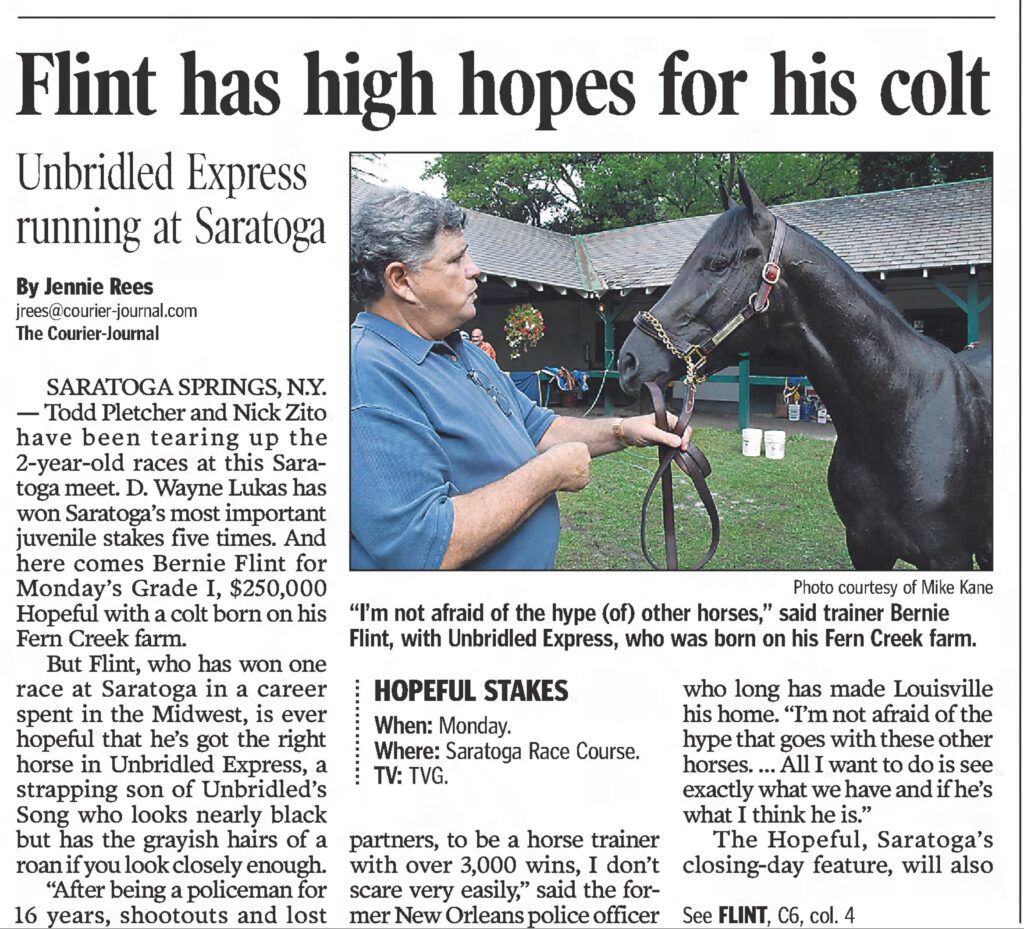

That includes the 2019 Indiana Stallion of the Year Unbridled Express, a son of Unbridled’s Song bred by Flint, Hillerich and the late Tom Conway. Unbridled Express beat Street Sense in a 2006 maiden race at Churchill Downs. Street Sense went on to win the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile and the 2007 Kentucky Derby. Unbridled Express sustained an injury when third in Saratoga’s Grade 1 Hopeful and, after two races following a 2 1/2-year layoff, was retired to what has been a highly successful breeding career in Indiana.

“One injury after another,” Flint said. “We decided to just go ahead and go with the Indiana program because he wasn’t quite good enough to stand in Kentucky. His foals are winning races hand over fist.”

Indeed, Flint and Hillerich’s stable is comprised of horses sired by Unbridled Express or out of his daughters. Hillerich said they have 19 horses together, including seven at the track and five broodmares.

“He’s doing well as an owner,” Steven Flint said of his dad. “He won a couple of $250,000 stakes last year.” He added with a laugh, “He probably should have done that a long time ago.”

Evangeline Downs recently feted Flint in absentia as part of the track’s Louisiana Legends Night.

“Listen, he deserves all the accolades he can get,” said Steven Flint, who now trains at Woodbine near Toronto. “I can’t even put it into words. He had no idea what a horse was when he started with quarter horses. He was a self-taught guy…. He had a long, long run where if he wasn’t on top, he was 1-2 for the training title, and no one ever spent a lot of money on babies for him.”

Stall, whose dad was a prominent horse owner, remembers being a kid and seeing Flint at the Fair Grounds.

“He was just so big. His voice was big. He was an intimidating guy,” Stall said, adding with a laugh, “You kind of had to cozy up to him at first, make sure everything was cool. That’s the thing I remember when I was really young.

“I used to talk to him a lot there at the end, in the parking lot at the Fair Grounds watching horses train,” Stall continued. “Very interesting guy. We’d talk about horses a little bit here and there. But we’d talk about the old days in New Orleans. His police stories were mind-boggling, and the people he knew. It was almost like lore. He was very front and center for the Mark Essex sniper (who killed nine people, including five police officers between Dec. 31, 1972, and Jan. 7, 1973).

“We used to always talk about watches. Did you know Bernie is an absolute expert on Rolex watches? But he knows about all watches. Bernie is very smart, brilliant, actually. He knows a lot of stuff about a lot of things. Those are the things I’d talk to him about, rather than, ‘Did you see who won the feature race yesterday?’”

When he turned in his NOPD badge to go into training full-time, Flint never expected the racetrack to be his life for another half-century.

“I never planned to be training into my 80s, believe me,” he said. “Lord knows how many races I really won. I was into it. I loved it. It meant the world to me. I was proud every time I won a race. I got as much of a kick out of winning a $5,000 claiming race as I did a $500,000 race.”

Related: The story behind One Mean Man (and he’s not named for Flint)